Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, billions of euros worth of Dutch exports have disappeared off the radar. On paper, the goods go to countries known to have a high risk of channeling sanctioned goods to Russia. But in practice, the goods disappear even before they arrive in those transit countries. That's according to data research by Hollands Welvaren based on data from the International Monetary Fund.

Were you forwarded this newsletter? You can subscribe yourself (free or paid) here.

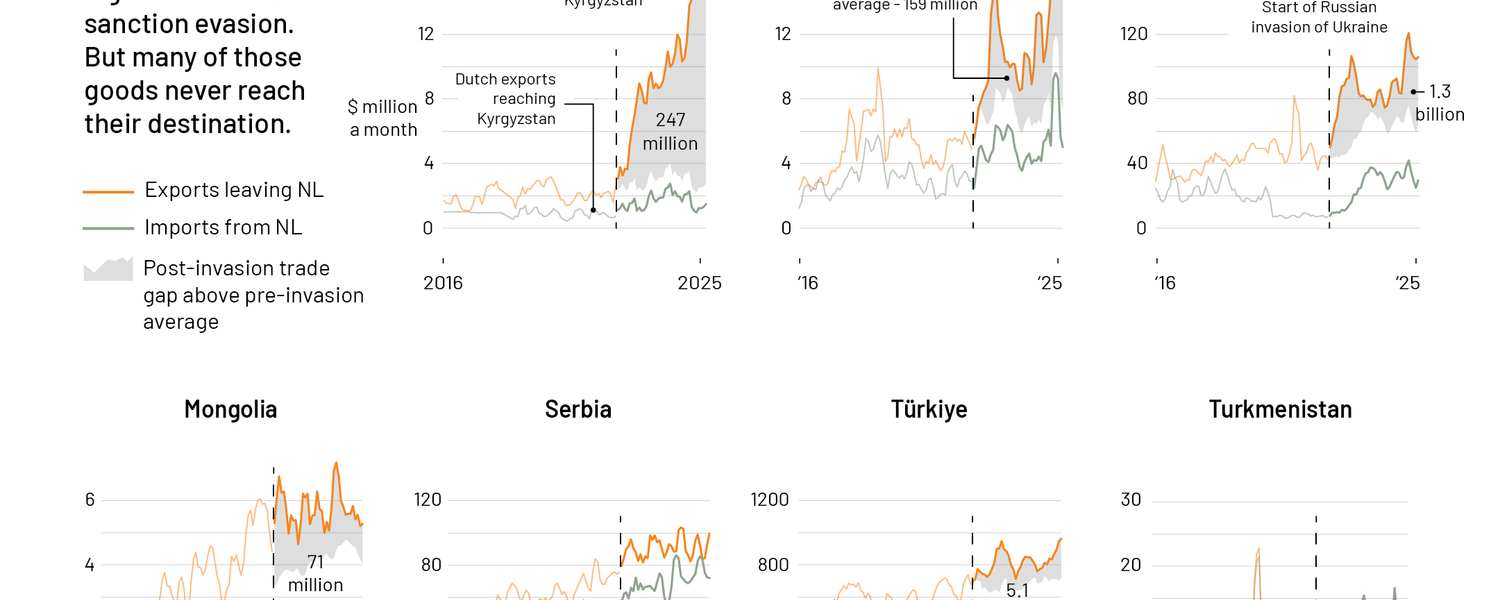

Kyrgyzstan is a beautiful, mountainous country. Not only tourists are increasingly finding the former Soviet republic. Dutch companies are also discovering the country. Exports to the country have increased tenfold in five years. In March of this year, over $16 million (€14 million) worth of goods were shipped to Kyrgyzstan.

At least on paper.

Because in the same month, the country registered less than $1.5 million from imports from the Netherlands. Ten times less. Export and import figures do tend to differ somewhat. A sea container can fall off a ship en route, an exchange rate can fluctuate, statistics offices can have different calculation methods, or customs forms can be tampered with.

But the differences between Dutch export figures to Kyrgyzstan and Kyrgyz import figures from the Netherlands are going to diverge at a most remarkable time: February 2022. That was the month the Russian military invaded Ukraine and the European Union launched a string of sanctions packages aimed at curbing trade with Russia. Since then, 18 sanctions packages have been declared. The sanctions mainly apply to goods that serve, or could serve, military purposes (dual purpose).

On top of the usual "gap" that has always existed between Dutch export and Kyrgyz import figures, nearly $250 million in Dutch exports to Kyrgyzstan have been "lost" since the Russian invasion, even before they arrived in that country.

For this calculation, Hollands Welvaren looked in the IMF' s International Trade in Goods database for figures on what the Netherlands exports to Kyrgyzstan. These figures were then compared in the same database with what Kyrgyzstan imports from the Netherlands. In theory, both figures should make that reasonably in line with each other: after all, what the Netherlands sends to Kyrgyzstan should equal what Kyrgyzstan receives from the Netherlands. But in practice, it is thus (increasingly) divergent.

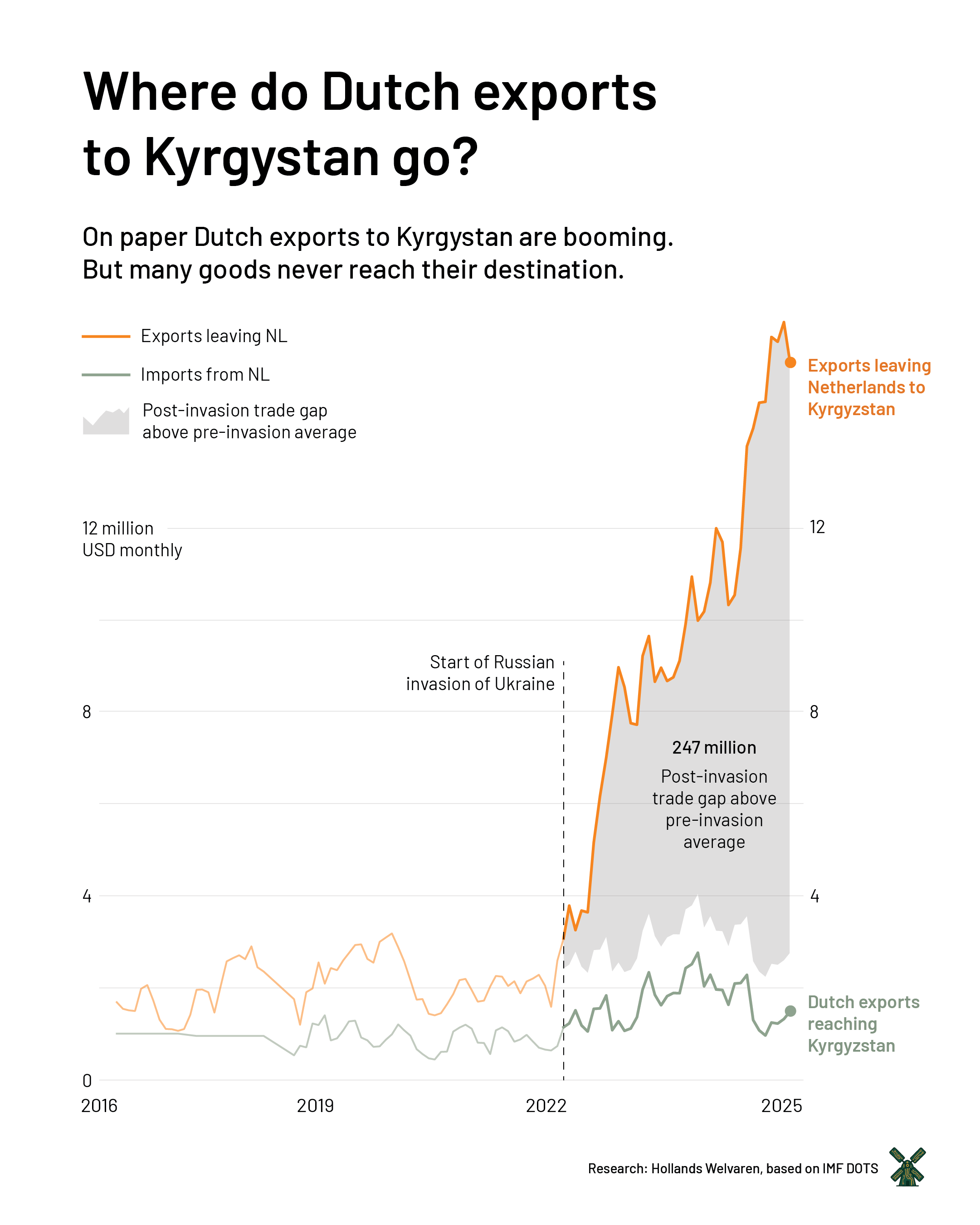

And Kyrgyzstan is not the only country where this is an issue. Hollands Welvaren 's analysis shows that Dutch companies have exported a total of nearly $7 billion (€6 billion at the end-July 2025 exchange rate) more to "countries with an increased risk of sanction circumvention," as the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) calls them, than those same countries have imported. In calculating this difference, the average "gap" between exports and imports that has always existed has been excluded.

That the sanctions against Russia are not foolproof has long been known. Late last year, CBS, in cooperation with the University of Groningen, found that seven countries have an"increased risk of sanctions circumvention": Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Serbia, Turkey and Turkmenistan. Goods exported from the Netherlands to those countries could be redirected back to Russia through that country.

This story is free to read,

but not cheap to make.

Get a paid subscription to Hollands Welvaren now and enable in-depth, independent journalism on the Dutch economy.

This is one of the last chances to subscribe for the reduced rate of 4o euros per year.

Among other things, CBS saw that many young and small businesses started exporting to those countries. And that especially exports of sanctioned goods rose. Like microchips to Turkey and Serbia and buses and truck (parts) to countries like Kyrgyzstan.

Hollands Welvaren 's analysis thus shows that many of those exports that CBS measures do not even arrive in those countries. This is true for five of the seven countries; only Serbia and Turkmenistan do not show this effect.

Are sanction rules being violated?

If such a country channels Dutch goods to Russia, that is not necessarily a violation of the sanctions law. That is a gray area. The sanctions apply to companies exporting from the Netherlands (and other EU countries). They have to do their best to prevent the goods from ending up in Russia (due diligence), but in principle, they can simply export to those high-risk countries. After all, no sanctions apply to exports to those countries.

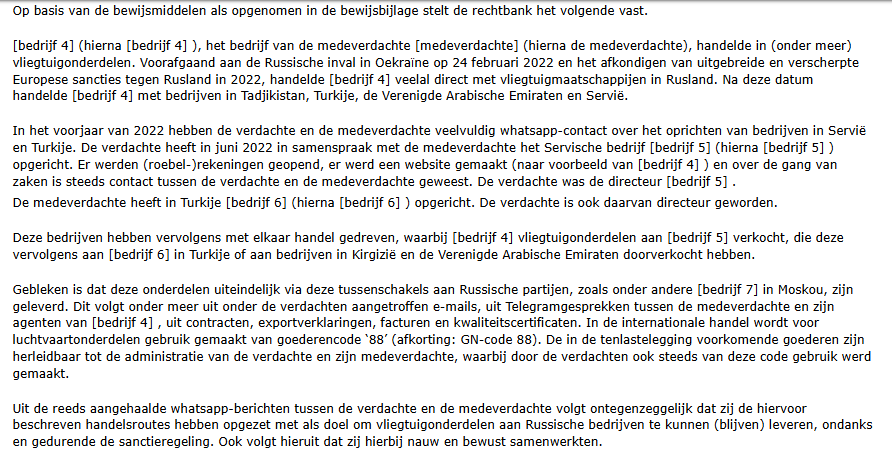

However, various court cases show that there are also Dutch entrepreneurs who knowingly set up sham constructions to those high-risk countries, with the intention of eventually getting the stuff into Russia. That, of course, is not allowed. You can read how that works in practice in the excerpt below from a court ruling by the Rotterdam District Court.

So whether sanctions are violated depends in part on the behavior of the Dutch companies that export. Have they made every effort to prevent their goods from being passed through, or is there malicious intent? Or is it somewhere in a twilight zone? After all, how far should you go in your investigation to see if your goods are not being resold? Should you go to Kyrgyzstan to see if your trucks are still running there?

That this analysis by Hollands Welvaren based on IMF figures shows that many exports to those countries do not even arrive there may indicate that many goods do not "accidentally" end up in Russia, but that sanctions are deliberately circumvented. After all, they never arrive at the destination entered on the customs papers.

It is not said that all these 'lost' exports ended up in Russia. After all, 'lost' is 'lost' if you don't know where it is. With some countries, such as Turkey and Kazakhstan, there was always quite a gap between what Dutch companies said they were exporting, and what officially arrived there.

'Exports' to high-risk countries still rising

In addition, exports to high-risk countries do not consist only of sanctioned goods. There are also still many goods that are still allowed to be transported to Russia (directly or indirectly). For example, the Netherlands still exports many medicines and flowers to Russia.

However, that pre-existing gap between exports and imports to Turkey and Kazakhstan has widened considerably since the sanctions packages took effect from February 2022. Dutch exports to Kazakhstan have more than doubled since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, while Kazakh imports from our country are roughly at the same level as before the corona hit. Also, exports to Turkey are rising, while Turkish imports from the Netherlands have been stable for some time. In addition, CBS noted in its December survey that some high-risk countries have "extraordinarily high exports of sanctioned goods.

It is notable that Dutch "exports" to these high-risk countries continue to rise. Many sanctions have been decreed at EU level, but their enforcement is up to the member states themselves. IMF data show, for example, that Poland did manage to close the 'gap' with Kyrgyzstan, while it continues to rise in the Netherlands. In a recent newsletter by economist Robin Brooks of the U.S. Brookings Institution, he argues that the Polish solution was fairly simple:

'How to stop this transshipment of goods? It is not that complicated. No additional regulations are needed, or additional export controls. It is much simpler. All it takes is a few phone calls from high-ranking people in the government to the companies involved. That will stop this transshipment almost immediately and is more or less what happened in Poland and Lithuania, both of which successfully stopped this trade. Source: Robin Brooks in his newsletter. Translation: Hollands Welvaren

What is the Netherlands doing against possible sanctions circumvention?

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs informs Hollands Welvaren that it is familiar with "the described phenomenon of a difference in imports and exports between the Netherlands and certain third countries. But the ministry says it cannot comment on its extent. Foreign Affairs also says that the government actively seeks contact with companies "if its own research or other signals indicate that (part of) their trade flows carry special risks of sanctions evasion.

Phone calls from the government, or not; Dutch companies are increasingly filling in customs papers that they are exporting to countries like Kazakhstan, Turkey, or Kyrgyzstan. And that their products never arrive there, oh well....

Read Foreign Affairs' entire response here

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is actively engaged in countering sanctions circumvention, including monitoring trade flows. The described phenomenon of a difference in imports and exports between the Netherlands and certain third countries is known to the ministry. However, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs cannot comment on which countries this applies to or to what extent.

In general, in what ways sanction circumvention takes place, there is no single answer. What is clear, however, is that circumvention routes are becoming more complex, with multiple intermediaries and other forms aimed at disguising flows of goods. This makes sanctions circumvention increasingly costly, which is a direct result of the effectiveness of sanctions designed to deny Russia access to critical goods destined for its defense industry and the production of military goods used in the war against Ukraine.

The Dutch government actively seeks contact with Dutch companies if its own research or other signals indicate that (part of) their trade flows pose particular risks of sanctions circumvention. The purpose of such discussions is always to provide companies with information and encourage them to take steps to reduce circumvention risks.