This article was written by journalist Jurgen Tiekstra. He is political editor at Binnenlands Bestuur and interviews for The New World. He also wrote the book: The climate debate as a laughing mirror.

After the fall of the first and only Schoof cabinet, it was free shooting for the opposition. Because GreenLeft-PvdA leader Frans Timmermans leads the largest opposition party, he was allowed to open the June 4 parliamentary debate, and thus attack. "No solutions have been found, not for the housing shortage, not for the nitrogen crisis, not for security," he berated.

D66 leader Rob Jetten heartily complemented him that day: 'In November 2023, more than 10 million Dutch people went to the polls. All those 10 million people wanted solutions. Solutions to the housing shortage, to migration and to better education. That voter now stands empty-handed.'

Volt leader Laurens Dassen's sigh afterward was the heaviest: "We sat and watched eighteen months of complete stagnation. Nothing really happened. (...) No homes have been added.'

It could never have been

Behold the oversimplification in political campaigning. It can be said to Dassen: during the little year that the Schoof administration was missionary, 80,000 homes will have been built. Because that is around the building pace in recent years. And to Timmermans and Jetten: the housing shortage has been worked on since at least Rutte-III, that is, since 2017. In that cabinet, D66's Kasja Ollongren was in charge of the housing dossier. Getting rid of the housing shortage takes so much time that Mona Keijzer as Housing Minister could never have solved the housing shortage already.

By the way: that Ollongren in Rutte-III, as Minister of the Interior , had to see to it that building took place, was because in 2010 the entire Ministry of Housing and Spatial Planning (VROM) had been disbanded by the then tolerant Rutte-I cabinet (VVD and CDA, with tolerant support from the PVV). It is precisely the Schoof cabinet that has restored this vanished department to its former glory, more than fourteen years later.

Continuous line

That many social dossiers indeed do not tolerate delay, VVD leader Yesilgoz seemed to acknowledge during the aforementioned House debate. She tabled a motion, "whereas it is irresponsible to stand still until the next elections," including on housing construction. Her appeal to the Cabinet was to press ahead on key issues. However, the motion was defeated. D66 voted in favor, but GroenLinks-PvdA and Volt, among others, did not.

Anyone who follows national politics a little more closely than merely through the news sees that Hague policy is often more of a through-line than a figure interrupted by each new cabinet. A new cabinet is usually not a revolution. Not even if it is a cabinet with real outsider parties, such as the PVV and BBB.

Between D66, CDA and BBB, there is little light here.

One example: last year, when two PVV members joined the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (Barry Madlener as minister and Chris Jansen as state secretary), the policy did not change from their two predecessors from the VVD. Madlener, too, wanted to meet the European water quality targets, due in 2027. Jansen, too, was concerned with PFAS pollution and dangerous rail freight.

Read the article Jurgen Tiekstra wrote earlier about the nitrogen problem here: Femke Wiersma: the misunderstood minister

The same goes for housing construction. Whether D66'er Kajsa Ollongren is the minister, or her successors Hugo de Jonge (CDA) and Mona Keijzer (BBB); they all want to build 100,000 houses a year and have at least 900,000 new homes standing by 2030. Keijzer is now defending in the Senate and House of Representatives laws prepared during the time of Ollongren and De Jonge. (Respectively, the Building Quality Assurance Act, and the Strengthening the Direction of Public Housing Act). Between D66, CDA and BBB, there is little light here.

Regaining control

Attempts to solve the housing shortage, as mentioned, have been underway since at least the ministership of Kasja Ollongren. In particular, her successor Hugo de Jonge and now Mona Keijzer are trying to do this by taking back the reins nationally, and taking direction away from municipalities and provinces for a substantial part. Hence the Law on Strengthening the Direction of Public Housing, which De Jonge designed and Keijzer is now implementing with some changes.

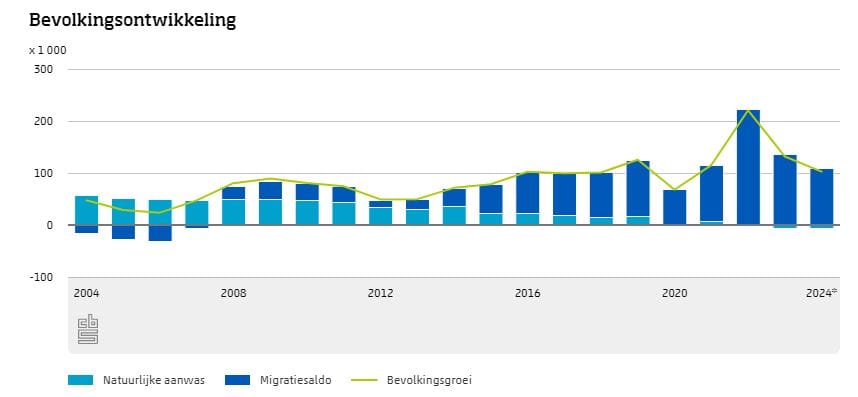

In recent years, housing construction was already increasing considerably. Although during his time as minister (2022-2024), De Jonge never reached the 100,000 new housing units. In 2024, 82,000 homes were added, in 2023 88,000. Among other things, what was disappointing was the war between Russia and Ukraine. This conflict caused higher material and energy costs, and then higher interest rates because the European Central Bank (ECB) wanted to use them to fight inflation.

Large population growth

In addition, the population grew faster than expected. The Association of Netherlands Municipalities (VNG) put its finger on the hefty number of labor migrants in the Netherlands: 'Between 600,000 and 800,000 labor migrants live and work in the Netherlands. Based on forecasts from the temporary employment industry, these numbers are going to increase substantially in the coming years.'

1 million additional homes in planning

But there was also a large influx of people for other reasons, such as the arrival in our country of many tens of thousands of Ukrainians.

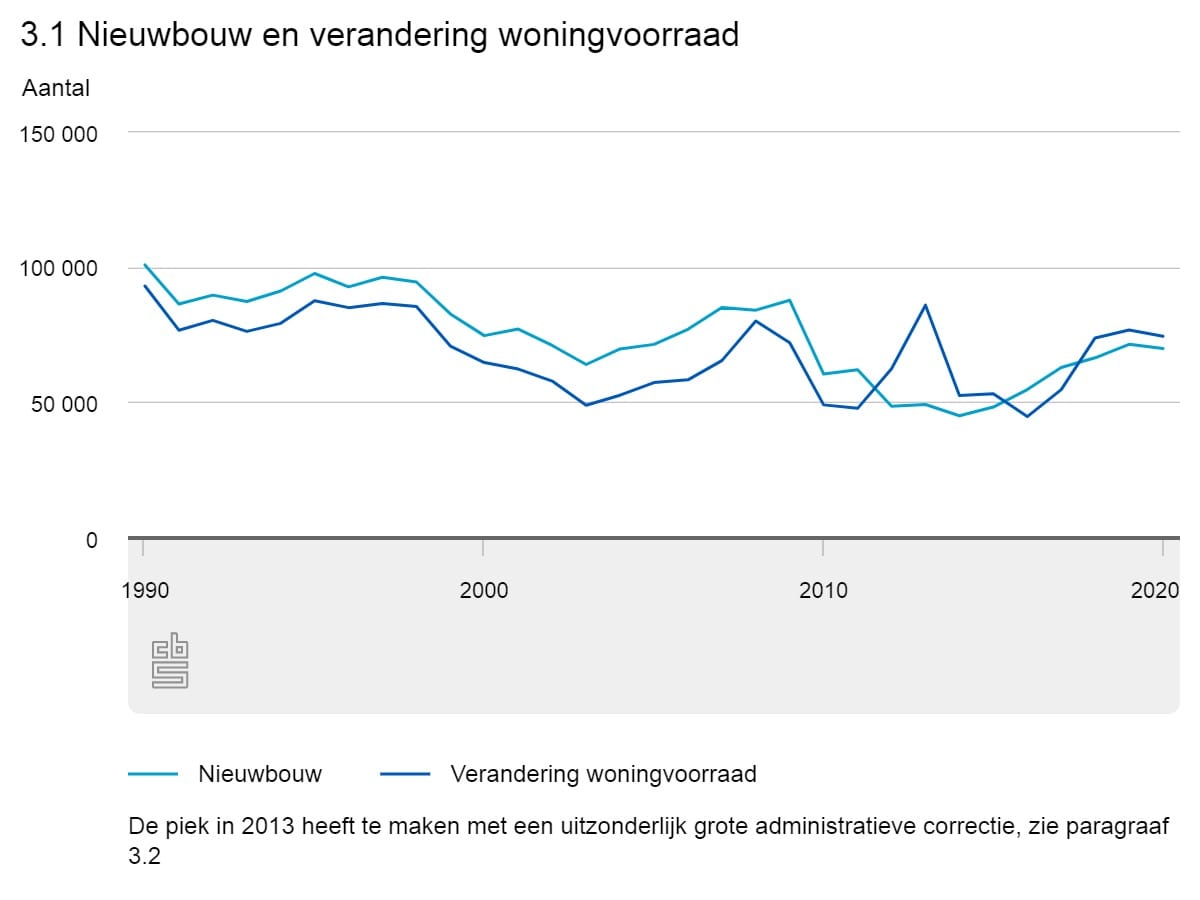

Minister Keijzer now thinks that construction will pick up in 2026, and that the dreamed-of 100,000 new homes will be hit for the first time in 2027. That would be a historic moment, because the last time this happened was in 1990. We are talking about the Lubbers III government, with Wim Kok as deputy prime minister. Hans Alders (PvdA) was then Housing Minister.

According to Keijzer, by the end of 2024 there were construction plans for 1,021,500 new homes through 2030. In theory, that is more than enough to meet the 100,000 new housing units per year.

Such a densely populated country

Building just under a million homes in a country as densely populated as the Netherlands is not easy, especially since the previous and current administrations were going to aim primarily for inner-city construction. It is easier to simply expand villages and cities. In addition, both De Jonge and Keijzer demand that two-thirds of new construction be "affordable. That means: 30 percent social rent, plus a good portion of rental and owner-occupied housing for middle-income earners. Those requirements make housing projects more difficult to make profitable.

That there is such a panic mood now is because the housing market collapsed after the 2008 financial crisis. Not only that, but housing policy also took a drastic turn. First, at the beginning of the Rutte era, the Ministry of VROM disappeared. Second, then CDA Interior Minister Piet Hein Donner worked on the controversial landlord levy, to be paid mainly by housing corporations. The tolerated cabinet quickly fell, so the second Rutte cabinet (with the PvdA) was given the dubious honor of introducing this levy. The goal, according to the explanatory memorandum: "budgetary revenue. Revenue was welcome in those years after the banking crisis.

Waiting times were already not mellow

The PvdA party voted in favor of this tax. Even an amendment by the SP did not receive support from the PvdA, although that legislative amendment was intended to prevent housing associations from getting into financial trouble because of the tax. Only more than a decade later was the landlord tax abolished again (this time it was a hammer piece, that is, without the need for a vote). But much earlier, in 2016, a scientific review had said that the levy was causing housing associations to shed tens of thousands of rental properties. Over seven years, the number of housing association properties decreased by nearly 115,000, another study, commissioned by housing association umbrella organization Aedes, found a few years afterward.

And the waiting times for social rental housing were already not glaring. Already in 2014, it took 8.7 years in Amsterdam to get a house. In West Brabant 3.8 years. In Den Bosch 6.2 years. In Hengelo 4.1 years, according to a study at the time. By 2023, the waiting time in the Amsterdam region had reached 12.1 years.

Those same years also saw little construction. In 2012, no more than 48,668 housing units. In 2013, more than 49,000. Only in 2016 did it pick up, with 55,000 homes.

That happened under the authority of then housing minister Stef Blok, from 2012 to 2014. His vision was diametrically different from that of the last two cabinets. In 2017, he told Het Financieele Dagblad. 'Almost all decisions on housing, such as zoning, are at the municipal and provincial level. VROM could actually have been abolished as early as 1965, after reconstruction.' Compare that with the previous and current administrations, which centralized housing decisions again and resuscitated the housing ministry.

The only political conflict

Anno now it is clear that outgoing minister Mona Keijzer is continuing the line of predecessor Hugo de Jonge. The idea that there should be a lot of construction is politically uncontroversial in The Hague. The only real political battle seems to be over how, and which approach is most effective.

A typical case is the province of South Holland, where a quarter of all new housing is to be built. Last year, De Jonge clashed with the GroenLinks-PvdA deputy concerned, Anne Koning. This was because the provincial government of South Holland wanted more social housing to be built than the CDA member felt was financially feasible, set stricter requirements for suburban housing, and used a less generous definition of which owner-occupied homes could still count as "affordable" for middle-income households. Ultimately, De Jonge forced South Holland to its knees with legal threats.

The wry harvests

De Jonge has since left, but Anne Koning is still there. She recently reported that construction in her province is still disappointing, despite having adjusted her policy to the CDA minister's wishes. King wonders if it will succeed in having a quarter of a million homes standing tall by 2030, as desired. Her reproaches primarily affect the now outgoing cabinet, because grid congestion and nitrogen bother housing construction. But she is also troubled by protected species, more expensive building materials and noise standards.

It's a telling story: on the one hand, homes have been coming out of the ground at a decent pace for years, on the other, there are dozens of hurdles that have to be taken again and again. Building at such a rapid pace is doggedly difficult in a country like the Netherlands. No cabinet has a magic formula for that. Nor is the fact that headache files like grid congestion and nitrogen add to the difficulties the fault of a government that has been in office for only a short year. They are painful dossiers that arose under previous cabinets.