In the wake of ASML, the chip industry has become the Netherlands' most important industry. With the rise of artificial intelligence, the Netherlands seems to be sitting on a gold mine. But reports of an "AI bubble" are also becoming increasingly serious. How vulnerable is the Netherlands?

In this story:

- How is the AI industry structured?

- What about the reports of an AI bubble?

- How vulnerable is the Dutch chip industry?

Did you know that you can also print money with AI? In November, Nvidia announced that it would invest $10 billion in Antrophic, the creator of ChatGPT competitor Claude. Microsoft is investing another $5 billion in Antrophic. In exchange for that $15 billion, Antrophic is purchasing $30 billion worth of computing power from Microsoft. Computers that run on Nvidia chips.

Ta-da, that's how $15 billion turned into $30 billion. How does Antrophic—which loses billions of dollars every year—scrape together the remaining $15 billion? Well...

Shell game

In recent months, numerous deals of this kind have been made in the world of AI. It is now almost impossible to keep track of who is investing in whom, who owes whom, and who is spending money they don't actually have.

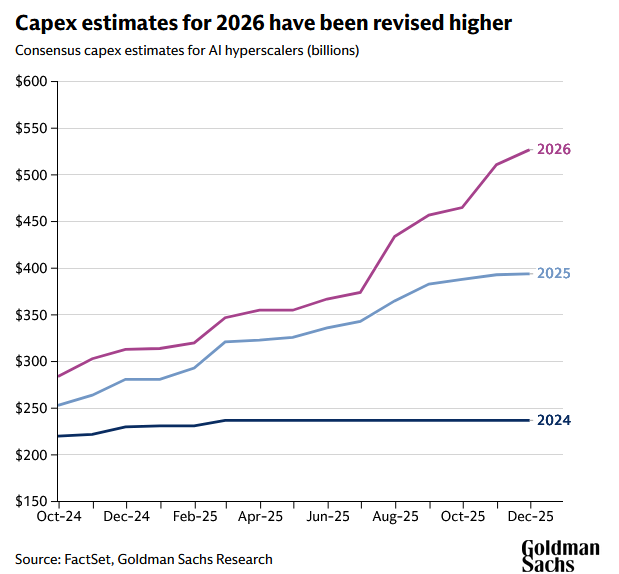

According to an estimate by Goldman Sachs, American tech giants will invest more than $500 billion in AI this year. But concerns are growing that this is a bubble that will eventually burst, if only because the American power grid is reaching its limits.

But while there is such a bonanza going on on the other side of the ocean, the mood in our own country is very different. Industry produced significantly more in August last year, but ABN AMRO sector economist Albert Jan Swart already noted in a commentary on the monthly purchasing managers' index:

Business activity may be growing thanks to the expansion of the chip market, although ASML's suppliers are also reporting other developments. Some suppliers say they are experiencing a significant decline in orders from the Veldhoven-based chip machine manufacturer. Demand for older machines in particular is disappointing, according to one of ASML's suppliers.

In December, the Financieele Dagblad reported that ASML's suppliers were feeling the pinch due to a decline in ASML orders.

How can those American Hosanna messages be reconciled with the Dutch misery? Shouldn't the Dutch chip industry be working overtime to meet all that American demand?

Phew, I've lost track. How does the chip industry actually work?

To explain this apparent contradiction, it is useful to first break down the chip sector a little. I have divided AI companies into five phases.

- Phase 1. Most people who use AI use ChatGPT, OpenAI's Large Language Model (LLM). Those who value ethics or want to do a lot of programming may use Antrhopics Claude. And for European chauvinists, there is the French Mistral.

- Phase 2. All these LLMs run in data centers that they often do not own themselves. These are often owned by external cloud providers such as Microsoft ( Azure), Oracle, or Amazon (AWS), known as 'hyperscalers'. But demand is growing so rapidly that new companies are emerging that are also going to build AI data centers, such as CoreWeave and the Dutch company Nebius (more on that later).

- Phase 3. These data centers are essentially large collections of AI chips. The most valuable company in the world is now chip designer Nvidia. Amazon and Google are also designing their own AI chips. But there are many more (smaller) players in this market, such as the Dutch company Axelera AI, which has already raised more than $200 million in growth capital.

- Phase 4. However, companies such as Nvidia do not manufacture these chips themselves. This is done in factories (fabs), such as those owned by Taiwanese company TSMC or Korean company Samsung.

- Phase 5. And those factories contain numerous different machines for manufacturing those chips. This is the phase in which the Netherlands excels. The best known is, of course, ASML's EUV 'chip printer'. But ASM also manufactures machines that help to produce extremely thin chip discs. And Besi manufactures machines that can bond chips together. Finally, there are also companies that make parts for those machines. ASML in particular has a long list of subcontractors, such as VDL, Aalberts Industries, and NTS-Group.

What about all those reports of an AI bubble?

The above overview is also useful for unraveling exactly what is going on with this AI bubble. Whether there is a bubble is, of course, the question. There are people who expect AI to become a kind of "superintelligence," putting us on the verge of unprecedented scientific breakthroughs and prosperity. Other experts , however, are fairly certain that AI is just hype.

But perhaps even more important than the technology is the money. Companies in that initial phase—such as ChatGPT's OpenAI—are not making any money. It costs them billions to develop language models. And often, customers pay little or nothing to use them, while OpenAI incurs costs to generate all those responses from hundreds of millions of customers. So they are dependent on financiers. And not just a little bit. OpenAI would like to raise around $100 billion. That money could come from venture capitalists or tech giants that want to use the language models themselves, such as Microsoft.

The amounts required have become so large that few companies and investors can afford to put them on the table. That is why OpenAI and Antrhropic are also considering an IPO, in order to raise money from a large number of different investors at once.

Achilles heel

The Achilles heel of these companies is therefore not even the technology—will ChatGPT be overtaken by Google's Gemini, for example?—but raising money. If billions from investors don't come in, it's game over. No money for new language models, no money to let people create funny pictures for free.

Even if the technology is excellent, there may simply be no money available. This can happen, for example, because investors become cautious due to a stock market crash, as was the case last year when Trump announced his tariff war. Or because of a drop in oil prices, which suddenly leaves Arab countries with much less money to invest. Or because of rising interest rates, as inflation remains high and the US government has a huge budget deficit (which makes borrowing money for investment more expensive).

Hyperscalers are also keeping their hands on the wheel

And that's not even mentioning the amounts needed by companies in the second phase, the hyperscalers that build data centers. Not only do they need tens of billions to build and purchase all those (Nvidia) chips, they also need electricity to run the data centers.

If you think the Dutch power grid is full, take a look at America. A large new AI data center consumes about as much power as a large power plant. But the power grid in America is so patchy that it is often impossible to simply transfer power from a power plant to a data center. So data center builders actually have to build a large power plant on their site as well. Not only does that cost billions more, but—you guessed it—there is also a shortage of gas turbines to run new gas-fired power plants.

So there's a good chance it will go wrong?

That is not necessary. If AI technology does indeed lead to a significant increase in productivity, and if venture capitalists continue to invest billions in companies with language models such as ChatGPT and Antrhopic, and if new data centers are built in time to meet all that extra demand for AI, and if there is enough power to run those data centers, then there will be no AI bubble at all. But the more that is invested in AI, the greater the chance that the sector will run up against one of those many limits.

However, these limitations mainly apply to companies in the first phase (language models) and the second (data centers). Chip companies further down the chain are actually in a much better financial position. At Nvidia (phase 3), chip orders are still pouring in.

Dutch canary in the coal mine: Nebius

One Dutch company at the forefront of the bubble debate is Nebius. This is the former parent company of the Russian search engine Yandex, which severed its Russian ties after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and settled in Amsterdam's Zuidas business district. Nebius now builds AI data centers and also provides additional services. It is therefore in the second phase of AI companies.

Read more about Nebius and why developments surrounding this company could say a lot about whether there really is an AI bubble and whether it is about to burst via the link below.

Money worries far away

At Nvidia, it's not quite like standing in line and paying cash, but it's not far off. In the first nine months of last year, Nvidia had $148 billion in revenue, of which a whopping $91 billion remained as profit. That's why Nvidia can make a mega-investment of $100 billion in OpenAI, and also invest billions in OpenAI's competitor Antrophic.

TSMC, which manufactures many of Nvidia's chips (phase 4), is also no stranger to financial worries. Of the $89 billion in revenue generated in the first nine months of last year, the bottom line was $47 billion in gross profit. But unlike Nvidia, TSMC does not throw its money around.

Thriftiness with diligence

An analyst at Goldman Sachs calculated that TSMC is only increasing its investments by 10%. That is money that could be used to purchase new ASML machines, for example. According to TSMC , these growth rates are sufficient to meet the future additional demand for AI chips. Something similar applies to South Korean chip manufacturer SK Hynix, which invests'disciplinedly'; in other words, not too much.

And that frugality of fabs trickles down to companies in the fifth phase, which make the chip machines.

This article is for paid members only

To continue reading this article, upgrade your account to get full access.

Subscribe NowAlready have an account? Sign In