The Netherlands is not a country of merchants, but of engineers. We earn our money not by trading cleverly, but by making things. From chip machines to Mars bars: the whole world wants them. Industry is crucial to our prosperity. But that does not mean we should blindly protect it for the sake of strategic autonomy.

First, a brief historical digression

Perhaps it went wrong in our own historical narrative. When you think of Dutch economic history, you quickly think of the VOC: how the Dutch sailed the world's seas and traded (and colonized and committed genocide). Or perhaps you think of the world's first stock exchange, in Amsterdam, where shares could be traded. Our windmills are a bit kitsch, something for tourists, people from outside. Even though they are such an essential part of our economic success.

When Cornelis van Uitgeest, a clever man, invented the sawmill, sawing wood for ships could be mechanized and no longer had to be done by hand. This enabled the Netherlands to build more and larger ships. As a result, the demand for foreign wood—and therefore trade—increased. And thanks to the improved ships, we could sail further and more often to trade. As a result, the Zaan region was able to grow into one of the first major industrial areas in the world.

No trade without domestic industry. And no industry without trade.

And now back to the present

According to Statistics Netherlands, the Netherlands earns €376 billion from foreign trade, which is more than a third of our total prosperity. Without that trade, we would all be a lot poorer. But if you peel back the figures, you see that much of that trade actually comes from our manufacturing industry.

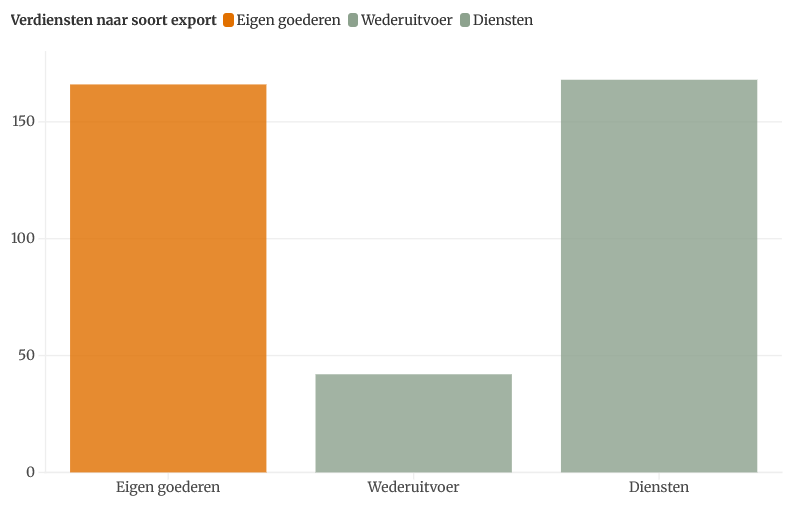

On paper, the Netherlands earns slightly more money from the export of services (€168 billion) than from the export of its own goods (€166 billion). However, some of these services are linked to the export of physical goods and industry. Twenty percent of the services we 'export' are transport services. Try getting an ASML EUV machine to Taiwan without a specialized carrier.

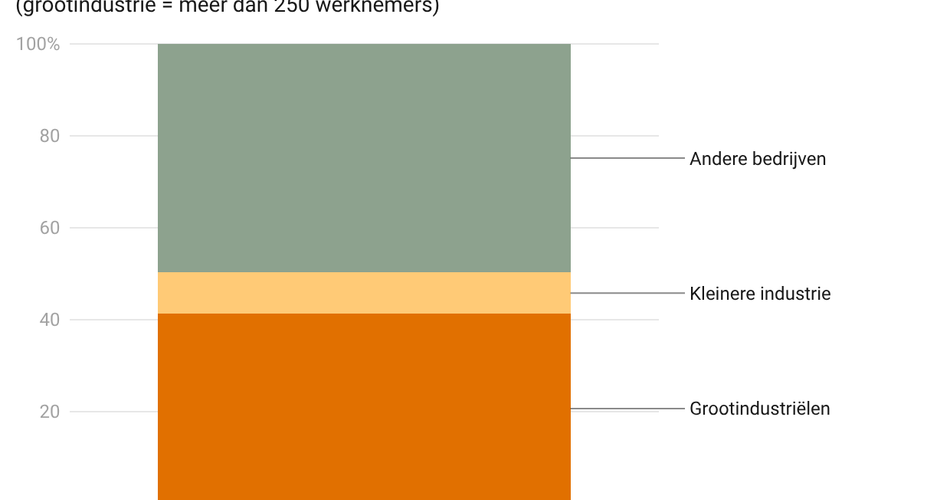

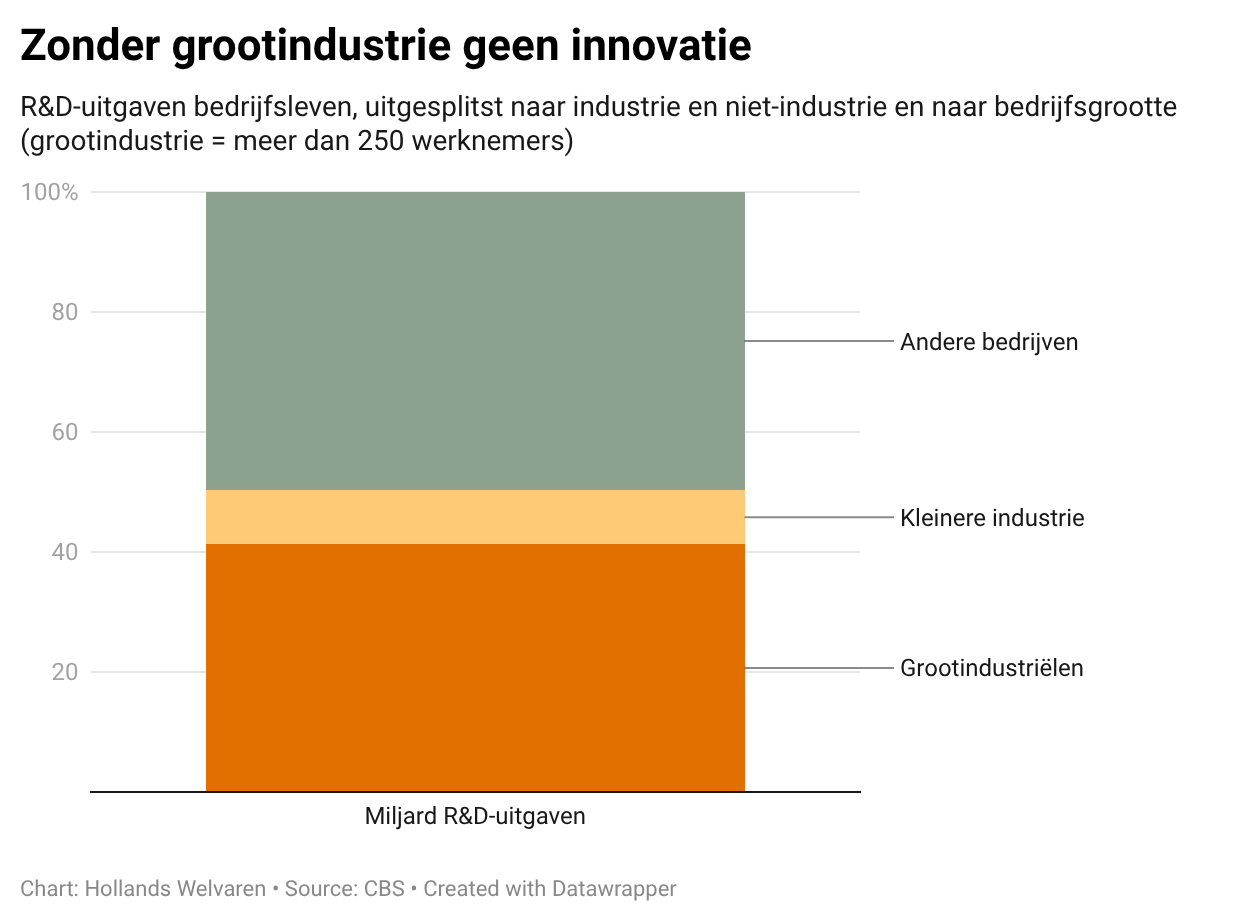

14% is also related to research and development. Some of this takes place at universities, but the majority (70%) is carried out by companies. And within the business sector, industry accounts for half of this. Large industrial companies in particular invest heavily. Without industry, our innovation would therefore suffer a blow.

What was true a few centuries ago still holds true today: international trade without a domestic industry is not worth much.

But what are these Made in the Netherlands products that everyone wants?

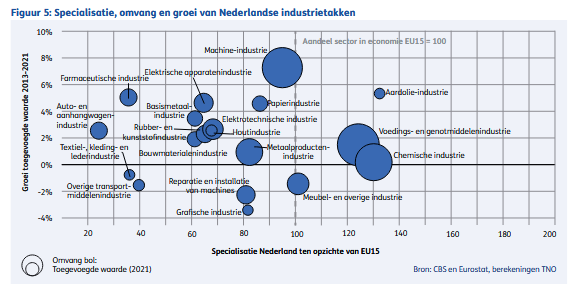

The Netherlands has a very diverse industry. From ASML to refineries, from trucks to chocolate cookies. Some parts of it are dirty, with high CO2 emissions; other parts are literally clean and are assembled in cleanrooms. Some industries are highly specialized (such as ASML's chip machines), while others mainly supply bulk goods.

A few years ago, TNO produced a clear overview of the size of each industry (the size of the spheres in the graph below), how fast that industry is growing (vertical axis), and how specialized the Netherlands is (horizontal axis). The food and chemical industries in the Netherlands are large in both absolute and relative terms, but growth is limited. From a European perspective, we do not have a particularly large pharmaceutical industry, but it is growing nicely. The fact that the machinery industry is the fastest growing is due, as you might expect, to ASML, among others.

How can the Netherlands pursue industrial policy when it is such a potpourri?

Until recently, politicians didn't care much about industry. We were supposed to become a service economy, and it was up to the international market to decide where all that dirty industry should be located. But due to the coronavirus crisis, Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and Trump's antics, strategic autonomy has suddenly become the buzzword. Everyone has their own interpretation of that term, but for the EU it means that it can simply do its own thing, without another country being able to blackmail us.

When we look at our own industry, we realize that we don't actually need a large part of it. Only a quarter of what our industry produces is purchased in the Netherlands. The rest is exported abroad. If a chemical giant closes its factory, or Heineken closes its brewery in Zoeterwoude, this is mainly a problem for Germany and America, not for us (except for the job losses, of course).

This article is for paid members only

To continue reading this article, upgrade your account to get full access.

Subscribe NowAlready have an account? Sign In