The revenue model of Dutch journalism has died. The paper newspaper subscriptions of baby boomers actually act as a kind of trust fund for the industry that pays out some money each year, but also makes the industry lazy in the process. Someday that revenue source will run out and large newsrooms will be unfundable. What will take its place?

The demise of the paper newspaper has been predicted for years. And yet it is still here. In some ways, newspapers even seem more alive than ever. They are much more present online, with podcasts, beautiful visuals, clever social media posts. More and more people are subscribing to newspapers digitally as a result. The years of sanitization of newsrooms seem to be coming to an end, and there are still plenty of newspaper newsrooms with more than 100 journalists running around.

But those appearances are deceiving. The newspapers are already knee-deep in quicksand.

Is it bad when journalism disappears?

The publishers of paper newspapers and magazines are still a crucial link in society's information supply. They employ some 3,400 journalists who provide the bulk of Dutch newsgathering (by comparison, NOS News employs 462 people).

Two publishing groups call the shots in newspaper country. The market leader is DPG, which publishes de Volkskrant, AD, Trouw and Het Parool. Mediahuis is the second, with titles such as De Telegraaf and NRC.

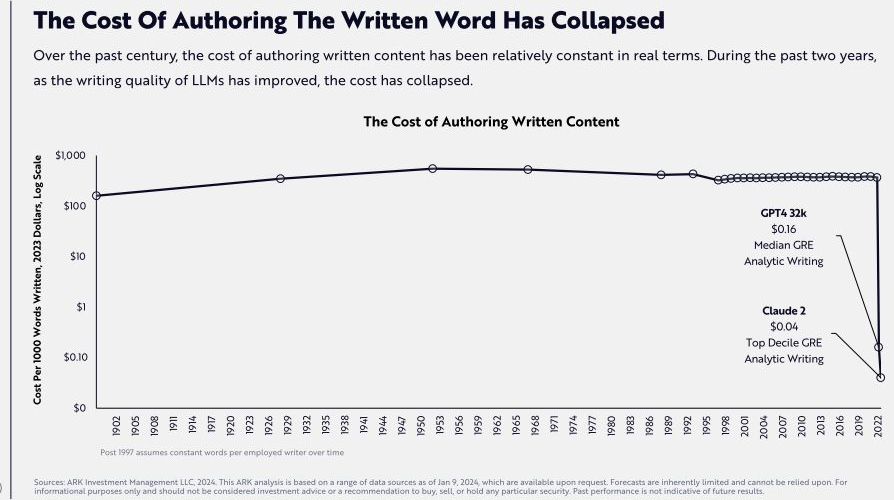

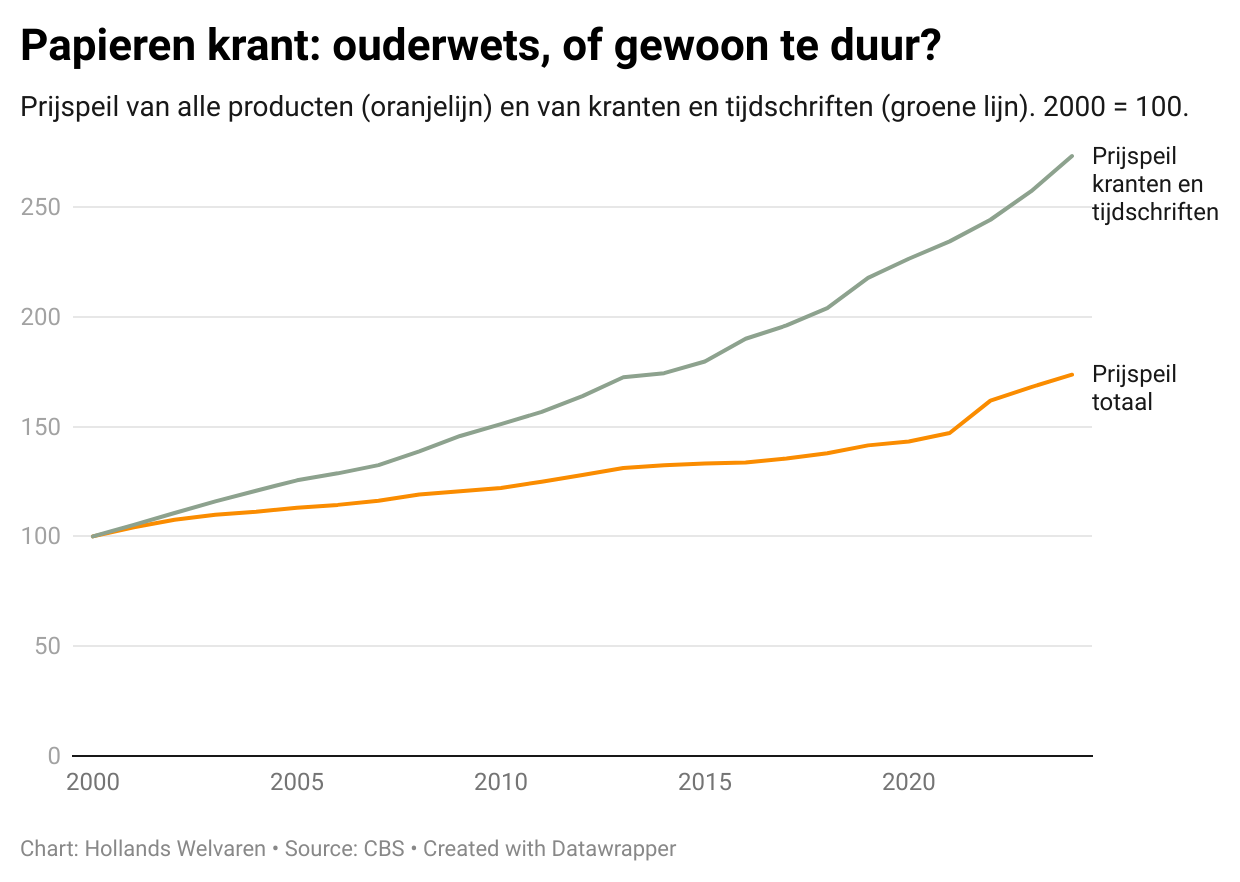

Last year, all publishing companies in the Netherlands together earned 1.2 billion euros. If you take inflation into account, that's a more than halving in twenty years. That is a gigantic blow. The fact that the newspaper companies are still afloat is largely because (especially older) readers are still very attached to their paper newspapers. This has allowed them to raise prices significantly. The price of a newspaper has risen twice as fast as other products in recent years.

That provides additional revenue for publishers, but also raises the threshold for new subscribers. A subscription to one of the country's two largest newspapers - not even the most elite ones - is already around 600 euros a year.

And that while the reader - who spends all day on his or her phone anyway - can also devour exactly the same copy digitally. For only a quarter of the price.

That immediately shows the problem. While the number of digital subscribers is growing rapidly, the money that publishers bring in from those subscriptions is much less. Of the 1.2 billion euro turnover, more than 900 million comes from paper subscriptions and paper ads, according to figures from industry association NDP.

Too much ballast

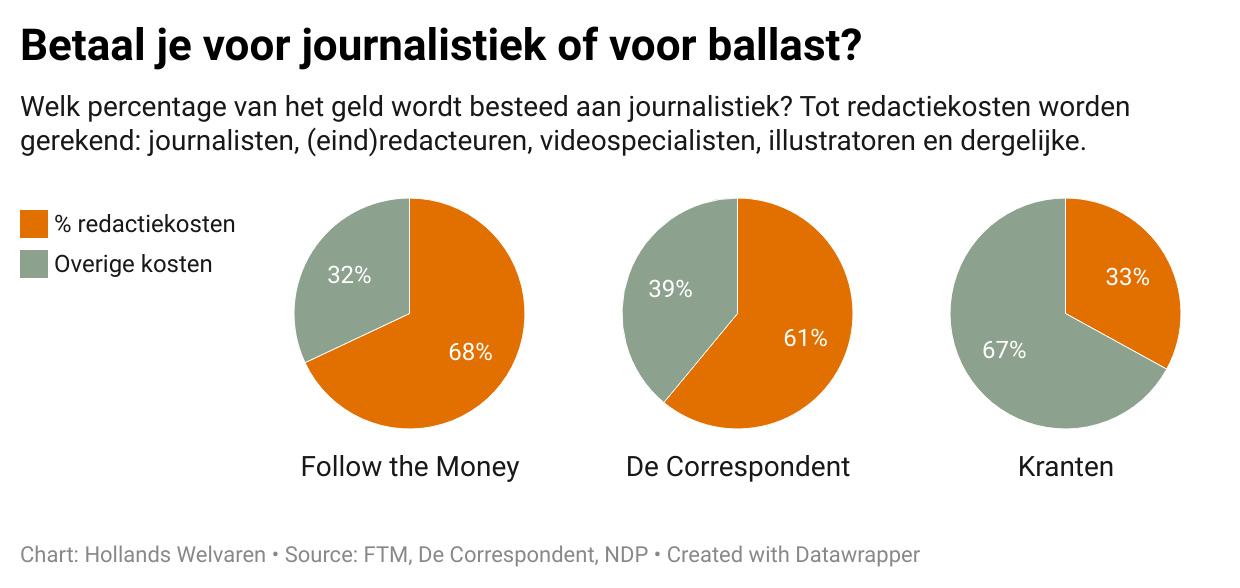

Thus, if publishing houses had to live on digital revenue alone, they would never be able to keep such large editorial departments alive. What's added to that is that publishing houses employ not only journalists, but also a lot of other people. People who, for example, sell ads, do marketing, or print the newspapers. Only a third of what readers pay for their newspaper actually goes to journalism. With online competitors, readers get roughly twice as much journalism for their money.

In other words, paper newspaper companies not only earn much less online, they are also twice as expensive as their online competitors.

The newspaper publishers themselves know that things are not looking rosy....

This article is for subscribers only

To continue reading this article, just register your email and we will send you access.

Subscribe NowAlready have an account? Sign In